By Erica Alini, National Online Journalist, Money/Consumer Global News, November 10, 2017

When it comes to making ends meet, having an income that keeps up with living costs is key. So what are the best jobs to be had in Canada, when it comes to wages and inflation?

Global News did some digging through the numbers. What we found is that there are at least two main stories to be told about the winners and losers of the Canadian labour market over the past 20 years or so.

The first one is that your best bet if you want a constantly growing paycheque is to become a manager. The second story is that your second-best bet for the past decade would have been to go into the resource sector or housing.

The Boss Has It Good

When we looked at which jobs performed best and worst compared to inflation, [Table 1 shows] what we found.

Table 1: Cost of Living – Wages Compared to Inflation 1997-2016

Inflation went up 42%

Best jobs

Management occupations ……………….. +95%

Care providers and educational, ………. +88%

legal and public protection support

occupations

Professional occupations in nursing …… +83%

Worst jobs

Retail sales supervisors and ……………… +33%

specialized sales occupations

(bellow inflation)

Labourers in processing, …………………. +33%

manufacturing and utilities

(bellow inflation)

Assemblers in manufacturing …………… +37%

(bellow inflation)

Source: Global News calculations based on Statistics Canada Data. Wages growth reflects normal median weekly wages.

Managers are the clear winners here – and that tends to hold true across sectors.

“Managerial occupations registered much higher wage growth than any other occupation,” according to a Statistics Canada study that examined similar data between 1998 and 2011. That trend seems to have held up since then.

And why have managers fared so well compared to everyone else? Economists aren’t entirely sure, said René Morissette, one of the authors of the study and research manager at StatsCan’s Social Analysis and Modelling Division.

Managers tend to be more educated than other types of employees, but neither those extra qualifications nor seniority tell the whole story, according to Morissette.

Most of that wage growth remains unexplained, but, according to some, part of it might have to do with a “greater ability for managers to extract rent,” said Morisette.

Certainly, Canada has had its share of headlines about exorbitant pay for senior executives.

But whether it’s stock options and generous bonuses or something else, one thing seems clear: Being at the top of the corporate food chain (or somewhat close to it, anyway) pays off more today than it did in the past.

At the other end of our chart are retail and manufacturing jobs that don’t require much schooling. For workers in those occupations, wages didn’t even keep up with inflation over the past two decades.

But lack of a university degree didn’t stop Canadians in other sectors from enjoying massive wage growth.

When Your Paycheque Goes “Boom”

When you look at wages by industry, the impact of the commodities and housing booms become apparent (see Table 2).

Table 2: Cost of Living – Wage Growth* 1997-2016

Best industries:

Mining, quarrying, and oil ……………….. +32%

and gas extraction

Public administration ………………………. +26%

Wholesale trade …………………………….. +22%

Construction …………………………………. +22%

Worst industries:

Manufacturing ………………………………… +3%

Information and cultural industries ……… +8%

Transportation and warehousing ………… +9%

*Median hourly wages for full-time employees, adjusted for inflation

Source: Statistics Canada

Regardless of education and tenure, if you’ve been working in mining, the oil and gas sector or the construction industry, you’re likely to have done quite well.

Wages in the resource sector rose by over 30 per cent between 1997 and 2017, net of inflation, according to data provided to Global News by StatsCan. That’s more than twice the across-industry average of 14 per cent.

Unsurprisingly, the wages of government employees also grew at a healthy clip of 26 per cent.

But tied for third place you’ll find the construction industry, where wages climbed on the back of soaring housing prices.

(As for wholesale trade, what drove the wage growth remains a bit of mystery. None of the experts consulted by Global News were able to provide an explanation.)

At the opposite end of the wage-growth spectrum is manufacturing, where wages barely kept up with inflation, the information and cultural industries (which includes the movie, publishing and broadcasting industries, among others), and transportation and warehousing.

The Resource Boom Was a Pay Boom for Canada

Both the resource and the housing boom put fat paycheques in the pockets of some Canadians. But the resource boom had much wider spillover effects.

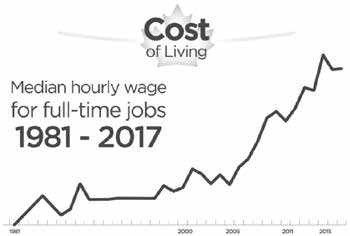

To gain an idea of the magnitude of those spillovers, it’s useful to look at Canada’s wages in aggregate. Figure 1 shows the percentage growth of Canada’s median hourly wage for full-time employees between 1981 and 2017.

Figure 1: Median Hourly Wage for Full-time Jobs, 1981-2017

Source: Statistics Canada (Global News), adjusted for inflation

Canada’s median wage rose by around 15 per cent over the period, but nothing much happened in the 1980s and 1990s. It isn’t until, roughly, 2005 that wages start on their upward trajectory.

About half of that growth is attributable to the resource boom, according to new research published by Morissette along with David Green of the University of British Columbia and Benjamin Sand of York University.

The resource boom created a number of well-paid jobs that didn’t require a university degree just as the manufacturing sector kept shedding good jobs, according to Green. But it also improved the bargaining power of many Canadian workers who didn’t move to the oilpatch.

Using Cape Breton Island in Atlantic Canada as a case study, Green, Morissette and Sand found that local wages rose by 13 per cent just as the oil boom was in full swing in Alberta.

“As many as one in eight men commuted from Cape Breton to Alberta for work at the time, with frequent direct flights from nearby Halifax to Fort McMurray,” Green noted in a recent interview with UBC.

That allowed others in Cape Breton to bargain for better wages by threatening to leave for the oilpatch.

“Long distance commuting for work in resource extraction can spread the effect of a boom over a much wider geographic region than previously suspected,” Green noted.

That’s not, generally, what happens with housing booms, which seem to have a more localized impact.

Mining and oil and gas extraction doesn’t generally happen anywhere near densely populated areas, which creates the need to ship in workers from far-flung parts of the country, said Green.

A housing boom, on the other hand, simply prompts more people who live in the area to take up jobs in construction and affiliated sectors rather than gigs in other industries.

So, should you drop out of university to take up a low-skill job in a booming sector?

After having a look at wages in the resource sector and the construction industry, you might be wondering if there’s any point in attending university. After all, why bother with years of extra school and costly tuition if there are well-paid jobs out there that don’t require a degree?

Tellingly, in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada’s three oil-producing provinces, the rate of enrolment of young men in higher education started flat-lining right around the start of the latest commodity-price boom, an analysis provided by Morissette to Global News shows. Many men either dropped out of school or decided not to pursue further education in order to go work in mines and oil fields.

In the short term, that is “a perfectly rational decision,” said Green.

But housing and resource booms go bust, he added, and in the long run higher levels of education are associated with higher wages and university degrees pay off better than technical diplomas.

So while taking up a richly paid gig as an oilsands truck driver or as a housing contractor in Vancouver may make sense for many, it’s important to have a plan in place for the post-boom phase of your working life, said Green.

And that plan will likely entail going back to school.

Our Comment

Of course, education should be about much more than jobs – increasingly so as we move through the 21st century.

Élan