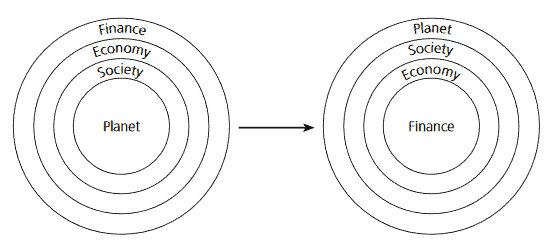

llustration from pages 4-5 in Whose Crisis, Whose Future? by Susan George

In Whose Crisis, Whose Future, Towards a Greener, Fairer, Richer World, Susan George uses “a series of concentric spheres set in a hierarchy of diminishing importance,” to vividly portray the “enormous task of people everywhere, an effort never before required in human history…to reverse the order of these spheres so that it becomes exactly opposite to the existing one”

In the first series, “the outermost and most important concentric sphere is labelled ‘Finance…and, finally, innermost and least important the sphere called ‘Planet.’ That is the order today.”

She argues that “our beautiful, finite planet and its biosphere ought to be the outermost sphere because the state of the earth ultimately encompasses and determines the state of all the other spheres within (pp. 2-3).

“So our daunting goal,” she argues, is to get from the existing sphere to the one that puts the “Planet” first and “Finance” last (pp. 4-5).

The concept of the paradigm is further described by Kalle Lasn.

And Now the Great Machine of Capitalism is Starting to Heave

By Kalle Lasn, integral-options.blogspot.com, February 15, 2011

There’s a tectonic mindshift going on in the science of economics right now, but you wouldn’t know it by tuning in to the likes of Martin Wolf, Paul Krugman, Andrew Sorkin, Lawrence Summers, Tim Geithner, Ben Bernanke, Dominique StraussKahn or most of the professors teaching Economics 101 around the world. These oldschool practitioners of neoclassicism are stuck in past, versed in only one language: the language of pure, unadulterated money.

As oil reserves dwindle and climate tip-ping points loom, they babble on endlessly about liquidity, stimulus, derivatives, bond markets, sovereign debt, AAA ratings and investment banker bonuses. They never say a word about melting glaciers, eroding coral reefs, rising sea levels, fizzing oceans or the methane that’s bubbling out of the arctic tundra. Like medieval theologians who argued endlessly about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, today’s economists argue incessantly about how economic growth can be sustained forever on a finite planet. Ten years from now, as the blowback from the externalities of their way of doing business repeatedly hammers us and global warming kicks in with a vengeance, we’ll look back in shock and awe – and wonder what it was about these logic freaks and their money narratives that so mesmerized us.

Five hundred years ago astronomers following Ptolemy’s geocentric model of the universe were tearing their hair out trying to make sense of all their calculations of the sun, moon and stars moving around above us in the night sky. It was only when Copernicus pointed out that we are not the center of the universe – the sun does not revolve around the Earth but rather the other way around – that all their convoluted calculations fell magically into place.

Today something eerily similar is happening in the science of economics: economists and lay people alike are realizing that our human money economy is a subset of the Earth’s larger bioeconomy rather than the other way around. Over the next few years, as this monumental shift of perspective kicks in, all the economic, ecological and financial craziness of the industrial era will evaporate, and a new sustainable way of running our planetary household will fall magically into place.

Economics students, especially PhD students, in departments around the world have a crucial role to play in ushering in this new paradigm.

Our Comment

This mind shift is indeed tectonic, reflecting an evolutionary leap in purpose and design.

Today’s dominant economic model is purported, by its champions, to be a science like physics, whose immutable laws can be understood and implemented through the language of mathematics. It puts money at the centre of the universe, and dismisses as “externalities” environmental and social consequences of economic policies. It depends on growth in a finite world, and is deaf to growing concerns about its cost/benefits record. It fails to appreciate the interconnectedness and the interdependence of related factors and downplays the political role in determining economic policies.

The Oxford dictionary defines economics as “the branch of knowledge concerned with the production, consumption, and transfer of wealth.”

“These oldschool practitioners of neoclassicism” would have us believe that the ‘market’ can be relied upon to regulate matters concerning these dimensions of economics.

The shift is to a model that realises “that our human money economy is a subset of the earth’s larger bioeconomy” and seeks to honour the priority of planetary welfare.

That change of perspective prompts us to question many aspects of our current system.

The following quotations from Thomas Piketty’s outstanding work, Capital In The Twenty First Century, are highly pertinent to the subject of this paradigm shift.

“By patiently searching for facts and pat-terns and calmly analyzing the economic, social, and political mechanisms that might explain them, it can inform democratic debate and focus attention on the right questions. It can help to redefine the terms of debate, unmask certain preconceived or fraudulent notions, and subject all positions to constant critical scrutiny” (p. 3).

“Economists of the nineteenth century deserve immense credit for placing the distributional question at the heart of economic analysis and for seeking to study longterm trends” (p. 16).

“It is long since past the time when we should have put the question of inequality back at the centre of economic analysis and begun asking questions first raised in the nineteenth century” (p. 16).

“The distribution of wealth is too important an issue to be left to economists, sociologists, historians, and philosophers. It is of interest to everyone and that is a good thing” (p. 2).

“There will always be a fundamentally subjective and psychological dimension to inequality, which inevitably gives rise to political conflict that no purportedly scientific analysis can alleviate. Democracy will never be supplanted by a republic of experts – and that is a very good thing” (p. 2).

“The history of inequality is shaped by the way economic, social, and political actors view what is just and what is not, as well as by the relative power of those actors and the collective choices that result. It is the joined product of all relevant actors combined” (p. 20).

“The discipline of economics has yet to get over its childish passion for mathematics and for purely theoretical and often highly ideological speculation, at the expense of historical research and collaboration with the other social sciences. Economists are all too often preoccupied with petty mathematical problems of interest only to themselves. This obsession with mathematics is an easy way of acquiring the appearance of scientificity without having to answer the far more complex questions posed by the world we live in…. The truth is that economics should never have sought to divorce itself from the other social sciences and can advance only in conjunction with them” (p. 32).

These books, by Susan George and Thomas Piketty, could do much to advance this crucial paradigm shift.

Endorse the call! Learn; act; change!

Paradigm: “a typical example, pattern, or model of something” (Oxford dictionary).

Élan