By Toby Sanger, Canadian Dimension, November 30, 2017

In their election platform and in ministerial mandate letters, the federal Liberals promised they would “establish the Canada Infrastructure Bank to provide low-cost financing (including loan guarantees) for new municipal infrastructure projects.”

This had the potential to be a positive initiative. The federal government can borrow at very low rates – significantly below provincial and municipal government rates. In mid-2017, the federal government could borrow for a 10-year term at 1.4 percent and over 30 years for just two percent. These rates are at or below inflation, and close to historic lows. The federal government could also potentially use the capacity of the Bank of Canada to finance public infrastructure projects directly, as had been done until the 1970s.

Unfortunately, it took very little time for the Liberal government to break its promise and succumb to the pressure of big money, turning this into a privatization bank instead.

In January 2016, two months after taking office, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau attended the annual World Economic Forum gathering of plutocrats in Davos, Switzerland. Here, he met with Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock Inc., the world’s largest investment firm, and other powerful bankers and investors at a breakfast organized by Dominic Barton, the global head of McKinsey Consulting.

Shortly after that, Liberal Finance Minister Bill Morneau announced the members of his Advisory Council on Economic Growth. The chair was Dominic Barton, and the vast majority of other members were either CEOs or investment executives. There was no one from labour or who might be seen to represent those that the Liberals so frequently claim they are standing up for: “the middle class and those working hard to join it.”

In addition to Barton, key members of Morneau’s council include Michael Sabia, CEO of the Caisse de dépôt et placement, Québec’s largest pension fund, and Mark Wiseman, the newly-appointed CEO of the Canada Pension Plan Investment Fund. Wiseman left within a few months to work at US-based Blackrock Inc. as Global Head of their Active Equities unit.

This group quickly went to work to recast the Liberal election promise to their own advantage.

Morneau outsourced policy-making about the bank from his department to this advisory council – and through Barton to McKinsey Consulting, which has largely been responsible for the content of the council’s flimsy reports. The council’s first set of recommendations included a proposal for an infrastructure bank that would rely heavily on expensive private-sector financing, and use it to privatize public infrastructure. The model for the infrastructure bank that Morneau proposed in his Fall Economic Update a few days later and then in his budget bill in April was, in all essentials, identical to this proposal.

Rather than welcoming low public borrowing costs as an excellent opportunity to build public infrastructure, these titans of private finance perversely saw low-cost borrowing as a problem. Why? Because it means that the returns private finance generates by lending directly to governments are low, with trillions in negative rate bonds.

Corporate Billions Sitting Idle

Corporations are sitting on hundreds of billions of excess cash in Canada and trillions worldwide – money they aren’t putting into productive investments. So corporations and other investors (including pension funds) desperately want to achieve higher returns. But economic growth is slow (because wage increases are so low and profits so high), which leads to fewer private-sector investment opportunities. So corporations are now turning to the cannibalization of public-sector assets and infrastructure through public-private partnerships or other forms of privatization, including the new infrastructure bank.

The great attraction of these public infrastructure investments for private finance is that high returns are effectively guaranteed for decades through ongoing government payments, and/or through tolls and other user fees. Most forms of public infrastructure involve some form of natural monopoly. This allows private owners to exploit them for monopoly profits – which is why they were established as public assets in the first place!

In another sordid twist, the briefing notes and presentation about the bank that were prepared for delivery by Trudeau and his ministers at a session for foreign investors were developed in conjunction with Blackrock officials, as Globe and Mail reporter Bill Curry revealed, using documents obtained through access to information. In effect, the Liberal government turned over the design and development of this bank to the very people who will profit most from it: the largest private sector and pension investment funds in the world.

More Than the Appearance of Conflict of Interest

As NDP finance critic Alexandre Boulerice said, “If this isn’t a major conflict of interest, I don’t know what else you could call it.” Even Conservative MPs such as former Surrey mayor Dianne Watts have been highly critical of Liberals providing billions in subsidies and turning over control of the bank to “powerful financial interests.”

And, breaking another promise they had made, the Liberals are ramming approval of the bank through Parliament by including it in an omnibus budget bill, a maneuver for which they had strongly criticized the Harper government and promised they would never adopt.

The Liberal budget bill proposes to finance the bank with an initial $35 billion in federal funding, but it will rely mostly on much higher-cost private funds for its financing dollars. The money from the federal government will be there to take a subordinate position and reduce the risk for private-sector investors. In effect, all the projects the bank finances will be privatized. Because private finance demands much higher returns from its investments than the rates at which the federal government can borrow, this means projects financed through the bank could easily cost twice as much over their lives than if they were publicly financed.

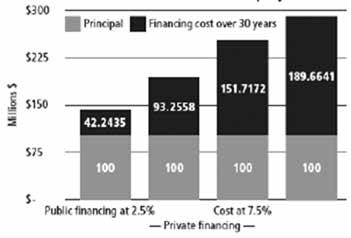

The financing costs for a $100 million project at a rate of 2.5 percent amount to just $42 million over 30 years. At a rate of 9 percent (approximately the return private investors expect from infrastructure investments, according to Caisse CEO Michael Sabia and others), the financing costs would total $190 million. This higher rate would quintuple the financing costs and double the total costs of a project – and demonstrates why private finance is pushing so aggressively for a privatization bank. (See Figure 1.)

(Figure 1: Private Financing Can Double the Cost of Infrastructure Projects)

Deeply Flawed

While private finance firms such as Blackrock Inc. may provide the financing up front, all the money to pay for this infrastructure will ultimately come from the Canadian people, both through annual availability payments from governments and through higher user fees, which will hurt middle- and low-income earners the most.

The Liberals have emphasized that the infrastructure bank will provide financing only for “revenuegenerating infrastructure” and for either new projects or projects that involve additional investment. They will very likely include toll roads and bridges, public transit, rail lines, water and wastewater, electrical grid and utilities. These will all involve higher user fees for the public.

Numerous critics have outlined major problems with the proposed bank:

- It will lead to massive privatization of public infrastructure;

- Projects will cost much more, so Canadians will get less bang for their buck;

- Projects will require significant increases in user fees, which will restrict access, and punish middleand lower-income earners;

- There will be little transparency and public accountability required of the bank and its projects or for its use of public funds. Information will be kept secret and will not be subject to the more stringent transparency and accountability rules that govern public projects, while those who disclose information could be subject to fines and jail time;

- The bank is restricted from having any representation on the board from the federal or any other governments, which means the bank will be controlled by private-sector interests, even though the legislation claims it will act in the public interest.

It is still unclear whether the federal government will have some say in the approval of projects, which is reason enough for the bill to be separated from the omnibus budget bill. But the Liberals have obstinately refused to do so.

In addition, the bank will be allowed to entertain “unsolicited bids,” which means that the for-profit interests in charge will be able to cherry-pick the public assets and infrastructure projects they think will be most lucrative for potential privatization. In the form currently proposed, the bank is a potential jackpot for private investors, while leaving the cupboard bare for the public sector.

The bank is also tasked with becoming a national centre of expertise and advice for governments on infrastructure projects. Canada needs national public infrastructure planning, but hosting this through a bank focused on privatization is absolutely the worst way to do it.

There’s no reason why the federal government can’t make the Canada Infrastructure Bank into a truly public infrastructure bank that would provide low-cost loans for large public infrastructure projects. The federal government already has banks and lending institutions that provide low-cost loans, financing, credit, and loan guarantees for housing, for entrepreneurs and for exporters.

The infrastructure bank could be established as a crown corporation with initial capital contributions from the federal and perhaps other levels of government and backed by a federal government guarantee. It could then leverage its assets and borrow directly on financial markets at low rates and then use this capital to invest in new infrastructure projects.

Better Ways

There are many different examples of public banks or lending institutions in Can- ada and around the world that provide lowcost loans for a variety of purposes. Canadian examples include the federal Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) for entrepreneurs, Export Development Canada (EDC) for exporters, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) for housing, and provincial financing authorities (which provide low-cost loans to municipalities). International examples include the World Bank, a range of regional investment banks and many other national investment banks.

Because they’re backed by explicit or implicit government guarantees, these banks and lending institutions can borrow on financial markets at low rates of interest (about 25 to 75 basis points above the backing government’s borrowing rate), which allows them in turn to provide low-interest loans. While the initial capital provided to establish them may be considered an expense or investment, the amount they borrow and subsequently lend out isn’t included on the government’s income statements, although it is recorded on consolidated balance sheets.

This approach would involve a slightly higher cost of financing than direct federal government borrowing, but it would be considerably below the cost of private finance. With federal backing, a national infrastructure bank could also provide financing at rates below those that municipalities can borrow at themselves, or through municipal financing authorities, which are about 150 basis points above federal government rates.

The project loans would be repaid by the proponents and could involve government payments, limited user fees where appropriate, and ancillary funding sources. But instead of relying on more expensive private sources for the bulk of its financing, and privatizing the projects, the infrastructure projects would be financed with much less expensive public financing and would remain public. And because the financing cost would be much lower, the annual funds required to pay for the project would likewise be much lower, with less need for user fees or for ongoing public payments.

This is the type of public infrastructure bank that the Liberals actually promised in their election platform. In the topsy-turvy way things have turned out, while the Canadian government has public banks and other lending institutions that take advantage of lower-cost public finance and government guarantees to support and subsidize private investments, the plan for a Canada Infrastructure Bank relies on much higher cost private financing for public infrastructure.

This illustrates how public institutions continue to be subverted to serve private profit by a predatory state predominantly controlled by the interests of private capital.

While it might have a friendlier face, there isn’t much difference between the probable consequences of this infrastructure bank and the mass privatization of public infrastructure planned by President Trump’s administration and similar initiatives carried out in other countries.

It is important to resist each privatization proposal and expose each project for who it will benefit and who it will hurt, but ultimately the pressure to privatize and cannibalize the public sector won’t abate until we achieve a more profound shift of power from concentrated private capital to a much more equitable economic order.

CUPE resources on the infrastructure “bank of privatization” can be found at cupe. ca/not-for-sale.

Our Comment

Yet another hen-house assignment for foxes!

How easy it has been to end-run the Bank of Canada – the infrastructure bank that belongs to all Canadians – the one mandated to serve the common good – with a privatization bank that will serve the privileged few with both a transfer of public wealth into their coffers and enormous potential to further enslave Canadians through unrepayable debt.

Anyone still willing to give the Canadian government “the benefit of the doubt,” ought to consider the way the “bank” was created, and the rules governing its operation.

The provision restricting the “bank” from having any representation on the board from government, entrusting the public interest to private-sector control, is an outright betrayal.

That such a “bank” should be “tasked with becoming a national center of expertise and advice for governments on infrastructure projects,” should be enough to provoke a national “aha” sufficient to shatter the carefully designed and preserved ignorance on which the plutocratic power of governments and corporations depends.

In her book, Beyond Banksters: Resisting the New Feudalism, Joyce Nelson identifies the architects of the Canadian Infrastructure Bank – institutions like BlackRock, the world’s biggest investment manager, and “consulting giant McKinsey and Company” and key advisors like Mark Wiseman, the CEO of the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), who “encouraged the [Canadian] federal government to look to places like Australia or the UK as examples of how Ottawa could utilise the capital of these global funds to meet its own infrastructure- needs” (p. 26), and who shortly moved on “to take a senior-leadership role” at BlackRock (p. 33).

The chair of Morneau’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth is Dominic Barton, who is “Canada’s so-called New Economy Czar” (p. 37).

He has been the global managing director of McKinsey and Company since 2009. McKinsey “advertises itself as a turn-around specialist, taking on failing companies and helping make them profitable again…it’s important to note, that apparently, there are times when a ‘turn-around specialist’ like McKinsey and Company actually can take a functioning organization and turn it into a disaster” (p. 39).

“Over the past few years, people in the UK have been in a pitched battle to save their beloved (publicly owned) National Health Services (NHS) from the creeping privatization plans outlined largely by McKinsey and Company” (p. 39).

Dominic Barton “pegged the infrastructure gap – the difference between what Canada needs and what it has – at a level as high as 500 billion” (p. 38).

He “believes Canada can lead the world in infrastructure building” (p. 38).

He told The Globe and Mail in 2009, “I believe very much in creative destruction” (p. 39).

He “fears [Canada] does not play a heavyweight role in international discussion of water’s geopolitical future.”

This is a mere sampling of the information to be gleaned from Beyond Banksters, and a glimpse of its insights into what we have to look forward to if we leave Canada’s future up to the CIB.

Élan